- Home

- Pablo Cartaya

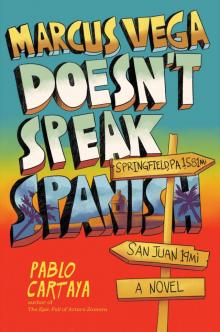

Marcus Vega Doesn't Speak Spanish Page 4

Marcus Vega Doesn't Speak Spanish Read online

Page 4

“The plaintiff, meaning Mr. Hobert?” says Principal Jenkins.

“I was standing right next to the defendant,” Danny corrects, “when the incident occurred. The plaintiff did indeed use a derogatory word to speak about the defendant’s brother and myself.”

“This isn’t a trial, Mr. Peña,” our principal says. “You don’t need to speak like that.”

“My apologies, Your Honor, I mean, sir.”

“Thank you,” Principal Jenkins says. “You can go back to class.”

Danny leaves and our principal stands up again.

“Okay,” he says. “This is what’s going to happen. Marcus, you are suspended until further notice. We will look at the details of this incident and consider all punishments, including expulsion.”

Stephen’s mom gives a weird standing ovation. “Finally, some justice.”

“And, Mr. Hobert,” the principal says to Stephen, “it sounds like you’ve been harassing younger students at this school. You will serve detention and community service for one week. We do not tolerate hateful language.”

“You’ve got to be kidding me. This is not the end of this,” Mrs. Hobert warns. “Not by a long shot.”

She storms out of the office with Stephen and his dad.

We get up to leave, but Principal Jenkins stops us.

“Hang on a sec,” he says.

He closes the door and says he wants to talk to us about Charlie.

“I worry,” he says, “that Marcus’s need to protect his brother may cause him to jeopardize his own schooling.”

“What do you mean, Mr. Jenkins?” my mom asks.

“Look, I know your son isn’t a bully, Ms. Vega. This kid helps out around the school, sets up for assemblies. He never complains. I do want you to stop making money off my rules, though. Do you understand?”

He points to my binder.

“That’s gotta be the first time in my thirty-plus years . . . Unbelievable,” he says, shaking his head. “Anyway, no more moneymaking schemes. Okay?”

I nod.

“I know Marcus is a good kid, Ms. Vega,” he says to my mom. “I know it can’t be easy raising two boys.”

“I don’t see how that’s relevant,” my mom says, raising an eyebrow.

“Point taken.” Mr. Jenkins rubs the back of his head. “Look, spring break is next week. I suggest taking some time to regroup and rethink some of Charlie’s educational goals.”

“What do you mean?”

The principal goes to his desk and pulls out a brochure. He hands it to my mom. She looks at it, and when she turns it over, I read the front: The Academy for Exceptional Students.

“It is a highly regarded school for individuals with special needs. They have academies all over the country.”

“There isn’t one anywhere near here,” my mom says, flipping through the brochure.

“There’s one in DC. That’s about two and a half hours away.”

“What are you saying?” my mom asks.

“Are you kicking my brother out of school?” I finally blurt out. “Because of me?”

“No!” he says, then turns to my mom. “Look, I just thought you should see that there are options out there for Charlie that would allow both children to thrive individually.”

“Thank you, Mr. Jenkins,” my mom says, handing the brochure back. “But my sons are fine here. We’re fine.”

My mom collects her bag and takes my hand.

“Ms. Vega,” Principal Jenkins says, insisting she take the brochure. “Just look at it. Please. It could be a good fit for your family.”

“You know, Mr. Jenkins, you fought really hard to make a place for Charlie at this school.”

“I did,” he says, “and now I’m looking out for Marcus.”

“I can take care of myself,” I say.

“You’re not a grown man, Marcus. You’re a kid. And I don’t want you to get into more trouble, trying to be your brother’s savior.”

I don’t like what Principal Jenkins is saying, but I can tell from his eyes that he believes he’s doing the right thing.

“You know what? I’m taking my other son home as well,” my mom says. “I hope you’re happy.”

Principal Jenkins shakes his head and tries to say something, but my mom has already walked off. I follow her outside to get Charlie.

“What are you doing here?” Charlie asks as my mom collects his things at his classroom. “What are you doing?”

“We’re going home, sweetie,” she replies.

“It’s schooltime,” he says. “I’m in school now.”

“I know, buddy, but we’re going to go home to spend some time together.”

We leave and Charlie continues to ask where we’re going. He doesn’t like when things change suddenly. We hop in my mom’s car, and the school disappears into the distance. My brother looks around, still wondering why he’s going home. My mom focuses on the road and doesn’t say anything.

I look at my hands. My right hand is swollen and the cold has started to crack the skin.

SIX

THE IF FACTOR

My mom was real young when she had me. She was in college when she met my dad, they got married, and then I was born. I don’t remember much about my dad, but sometimes I see flashes in my head that feel so familiar. Like my dad making funny faces at me as I sit at a table, eating peas or something. I see him making these faces while sticking out his ears and bouncing around. I guess he’s trying to make me laugh because I won’t eat the peas. I see him take my spoon and pretend to eat my food. Saying, “Mío. Esto es mío.” I don’t know Spanish, but I somehow know he’s saying my food is his. Then he gives me the spoon, and younger me scarfs down the peas.

I don’t remember my parents fighting or why they even split up in the first place. My mom never talks about it. As I got older I figured that he just didn’t feel like being around. Maybe he was ashamed or something. That thought made me angry. It pulled at me and kept me stuck in one place at the same time.

I look up and catch my mom watching me carefully from the doorway. I wonder how long she’s been standing there.

“Hey,” she says.

“Hey,” I reply.

“So, I should be pretty mad at you.”

“Yeah.”

“I have to take a week off of work, possibly more.”

I nod.

“Your principal is suggesting a private school for your brother because of how you behaved today.”

I don’t respond.

“And this new school happens to cost about a quarter of my yearly salary.”

I stare at the chipped crown molding wrapped around my bedroom. The powder-blue walls that my mom swears one day we’re going to repaint. The window that never shuts completely. The gray sky outside. The way the light casts a shadow across the wood floor. It reaches all the way to my desk from the entrance of my room.

“We really need to repaint this room,” my mom says for the hundredth time. And for the hundredth time, I tell her I don’t care.

“Don’t you want any posters at least?”

I tell her no. My room doesn’t have a lot of stuff in it. Honestly, clutter bothers me. I have a desk. A chair. A computer. That’s about it. I have a few framed pictures of Charlie and me and some of my mom. In my closet, I have a bag of old stuffed animals. I keep meaning to give them away now that Charlie is too old for them, but I haven’t gotten around to it.

“This isn’t working, is it?” my mom says.

I finally look at Mom to try to understand what she means.

“I work too much. We’re always trying to fix something around this old house, and saving money in case something else breaks—which, by the way, no more side businesses, okay?”

“Okay.”

“I mean, M

r. Jenkins is right, you know? You’re a kid. I’m putting all this responsibility on you and you’re fourteen years old. What kind of mom am I?”

“Don’t worry about that, Mom,” I tell her. “Forget what he said. He doesn’t know us.”

“No, sweetie,” she says. “You shouldn’t have to do all that. Look what happened. You’re crumbling under the weight of it all.”

“I’m fine, Mom.”

“No, you’re not,” she says. “We need to get away from here and out of this rut. Just the three of us. We need to regroup.”

“Where are we going to go? We don’t have money for a trip.”

“One of the great things about my job is that we can fly for free if we really want to. Where would you like to go?”

“Puerto Rico,” I say. My mouth fires off before my thoughts can catch up.

“Now, why would you want to go there?”

“You know why,” I tell her.

“To visit your dad? No! Goodness no.”

“Why not?” I reply. “You just said that you work too much and everything’s always broken and everything’s a mess.” I could feel my face getting hot. “Why shouldn’t he help us?”

“Because your father has had plenty of opportunities to help and he hasn’t, Marcus. Not once.”

“But have you called him? Sent him pictures? Told him to come visit?”

“Marcus, we’re not going to see your father. Okay? End of discussion.”

I look out the window and ignore her.

“But,” she says, walking over to me and placing her hands on my shoulders, “Puerto Rico isn’t a bad idea. We could fly for free and stay with your great-uncle Ermenio in Old San Juan.”

“The guy who sends the Christmas cards every year with five bucks for me and Charlie?”

“Yeah,” she says. “I loved spending time with him when your dad and I were together. He hasn’t seen you since you were a baby. And he’s only seen pictures of Charlie. I could call him,” my mom says. She sounds serious.

“So, we could stay with Great-uncle Ermenio and go see Dad.”

My mom takes a seat at the edge of my bed and pulls at my toes. She’s done this since I was little.

“Honey, your dad moves around a lot. And I only have an email for him. The chances of him responding are zero to none.”

“But if we’re going to go . . .”

“We haven’t even made the decision to go! We’re just talking.”

“Mom, we have to go,” I say, sitting up. “What if that school for Charlie is really good? What if Dad can help us pay for it?”

“Marcus, what are you going on about? The closest school is in DC. Are we supposed to move?”

I shrug. “Why not? What do we have here anyway?”

My mom scoots close to me. “This house, honey. We can’t just move.”

“What if you got a job in DC? What about . . . I don’t know.”

I notice my mom has been holding the brochure Principal Jenkins gave her. Maybe she’s been thinking about it like I have.

“Can I see that?” I ask, reaching out. My mom hands it to me.

“Look, there’s one in New York, two in Boston, one in St. Louis,” I say, pointing. “There’s even one in Miami. We can move anywhere, Mom. You work at one of the biggest airlines in the world. You can get transferred. And Dad can help us pay for Charlie’s school. We can get out of this town.”

“Honey, honey, relax. Look, a lot happened today.” My mom exhales.

“Can you call work?” I ask. “See if you can get us a flight? Call Uncle Ermenio. . . .”

“Marcus . . .”

“Then email Dad. . . .”

“Whoa, slow down. First, you’re suspended. You should be grounded, not thinking about vacation.”

“Come on—”

“Second,” my mom interrupts, “suddenly you have this interest in seeing your father?”

I nod.

“Why?”

“I dunno,” I say, looking at my closet door.

My mom grows quiet for what feels like a really long time. Then she lets out a big exaggerated breath.

“Let me think about it,” she finally says. “But don’t get your hopes up.”

“I won’t.”

“If we end up going. If. It’s not definite. If.” My mom points to me. “I want this to be a reset for us. You. Your brother. And me. Got it?”

“Got it,” I say, feeling excited.

“If,” she repeats. “If we go.”

“Right,” I say. “If.”

My mom walks out of my room and I hear her talking to herself again.

“A chance for us to get out of our routine,” she mutters. “Spend time together as a team.”

“Hey, Mom?” I say, getting up and going to my computer.

“Yeah?” She turns to face me.

“Where was the last place he was at?”

“Marcus, are you even listening to me?”

“Yes, family vacation. Go team go. So, do you remember?”

“The last place was at your uncle Ermenio’s house in Old San Juan.”

“Do you have an address?” I ask, typing “Old San Juan, Puerto Rico” into Google.

“Bordering on annoying now, Marcus. You’re bordering.”

“Come on, Mom,” I tell her. “Aren’t you even a little curious to see where he is?”

“I’m not even sure I can get three plane tickets, Marcus. And what if Ermenio doesn’t have room for us? There are a lot of ifs to figure out.”

“Okay,” I say, still browsing online.

My mom pecks me on the cheek and leaves my room. I search my computer for a while longer and finally turn it off and head to bed. I don’t know why my dad never answers my mom’s emails.

I hadn’t thought about connecting with my father. But now I want to send him an email. He might respond if he knew we were coming. It’s another if that needs an answer.

SEVEN

PRESSING SEND

The next morning, I step into my closet, pull out my sneakers, and lace them up. I got a new pair of kicks for Christmas, and they’re already starting to wear down. Some kids have six or seven pairs of sneakers. They like to show them off. I see them bragging to each other during lunchtime. Especially Stephen. He comes in with a new pair every other week. I have a few, but I usually wear the newer ones consistently for about a month straight. Every day. I like the way they mold to my feet the more I use them. It’s like the shoes get comfortable with me and vice versa. We fit better the more time we spend together. Anyway, what’s the point of having shoes that are barely used? I bet Stephen doesn’t use his sneakers more than four or five times, if that.

My mom walks by and stops at my door, nearly spilling her coffee.

“Whoa! Just where do you think you’re going, mister?”

“Walking the kids to school,” I tell her as I finish getting ready.

“Marcus, did you hear anything that Principal Jenkins said yesterday? No more business ventures.”

“Mom, these kids paid through the end of the week. That’s today,” I tell her. “I have to fulfill my obligation to them.”

“Marcus, you are charging kids to walk them to school. Do you not see the problem with that?”

“They asked me to do it,” I reply. “And I give them a fair price.”

“You are not a private security company! Marcus, honey, this isn’t a joke.”

“I never said it was,” I say. I can tell my mom is getting frustrated. She starts to rub her neck, which has gotten red. Mine gets like that when I’m angry too. “I have to honor my commitment,” I tell her. “It’s just today. Then that’s it.”

My mom watches me carefully, then shakes her head. “Marcus, we have to lay low. I’m worried. I really w

ant you to stay out of sight while all of this gets sorted out.”

“Just today, Mom. I promise.”

She exhales, then takes a sip of her coffee. “Okay. Just be careful. Stephen’s mom is looking for any opportunity—”

“I will,” I say as I pass her to get to the stairs.

“Grace said she would do a house visit later for Charlie.”

“Cool,” I say.

“She’s really great,” Mom says, walking down the stairs. She watches me as I start outside. I turn around before I leave.

“I’m sorry for all that went down, Mom,” I say.

“You shouldn’t have punched him, Marcus. That’s never a good solution. I’m worried now that the kids you’re walking—”

“Those kids wouldn’t say anything,” I tell her. “When they walk with me, Stephen doesn’t pick on them.”

“That’s what I’m afraid of,” she says. “That he’s going to be waiting around to taunt you.”

“Don’t worry, Mom. It’ll be fine.”

I see the concern on her face. She thinks Stephen is going to push me over the limit again.

“Expulsions stay on your permanent record, Marcus.” I can tell that she’s trying to stall.

“Mom, I gotta go. I’m going to be late.”

“And you’re so smart. You’ll be able to get into any good school.”

I’m going to high school next year. It’s why I’ve been thinking that maybe the academy would be better for Charlie. When I graduate, he’s going to be left alone in middle school. Stephen won’t be there anymore, but there’s always another Stephen waiting in the wings.

“You know what? I’m going to start looking into our family trip,” she declares. “I think there might be a silver lining to all of this.”

“Cool,” I tell her, and give her a kiss on the cheek before finally heading out.

“Be careful, sweetie,” she says.

“I will,” I tell her.

My mom looks at me over the rim of her coffee cup as she takes a sip. Then I hear her close the door behind me.

The cold air hardens my cheeks as I make my way to Danny’s house. When I get there, he’s on his lawn, throwing little twigs at a tree.

Each Tiny Spark

Each Tiny Spark Marcus Vega Doesn't Speak Spanish

Marcus Vega Doesn't Speak Spanish